After viewing the above video, reflect on the following questions in a well-written post on your Reflection Blog.

- Do you agree with Tom Wujec's analysis of why kindergartners perform better on the Spaghetti Challenge than MBA students?

- Can you think of any other reasons why kids might perform better?

- In your view, why do CEOs with an executive assistant perform better than a group of CEOs alone?

- If you were asked to facilitate a process intervention workshop, how could you relate the video to process intervention skills?

- What can you take away from this exercise to immediately use in your career?

The Marshmallow Challenge "forces people to collaborate quickly” and many go about it in a patterned, predictable way that can be charted (Wujec, 2010). Most teams waste a good deal of time vying for power, which is followed by a planning stage, a building process, and at the end as time draws to a close, the team works an integral piece of the challenge in: adding the marshmallow to the top. This is why most adults - particularly educated adults with clear leadership roles in their organizations - fail to sustain standing structures. Tom Wujec said he has done this with over seventy groups. Surprisingly there is a clear classification of which groups of people perform better and who perform the worst. Kindergarten students do better than just about every adult group besides architects and engineers (thankfully).

What makes these seemingly feeble minds so extraordinary is what they don't know how to do yet: KIDS DON'T CARE ABOUT POWER.

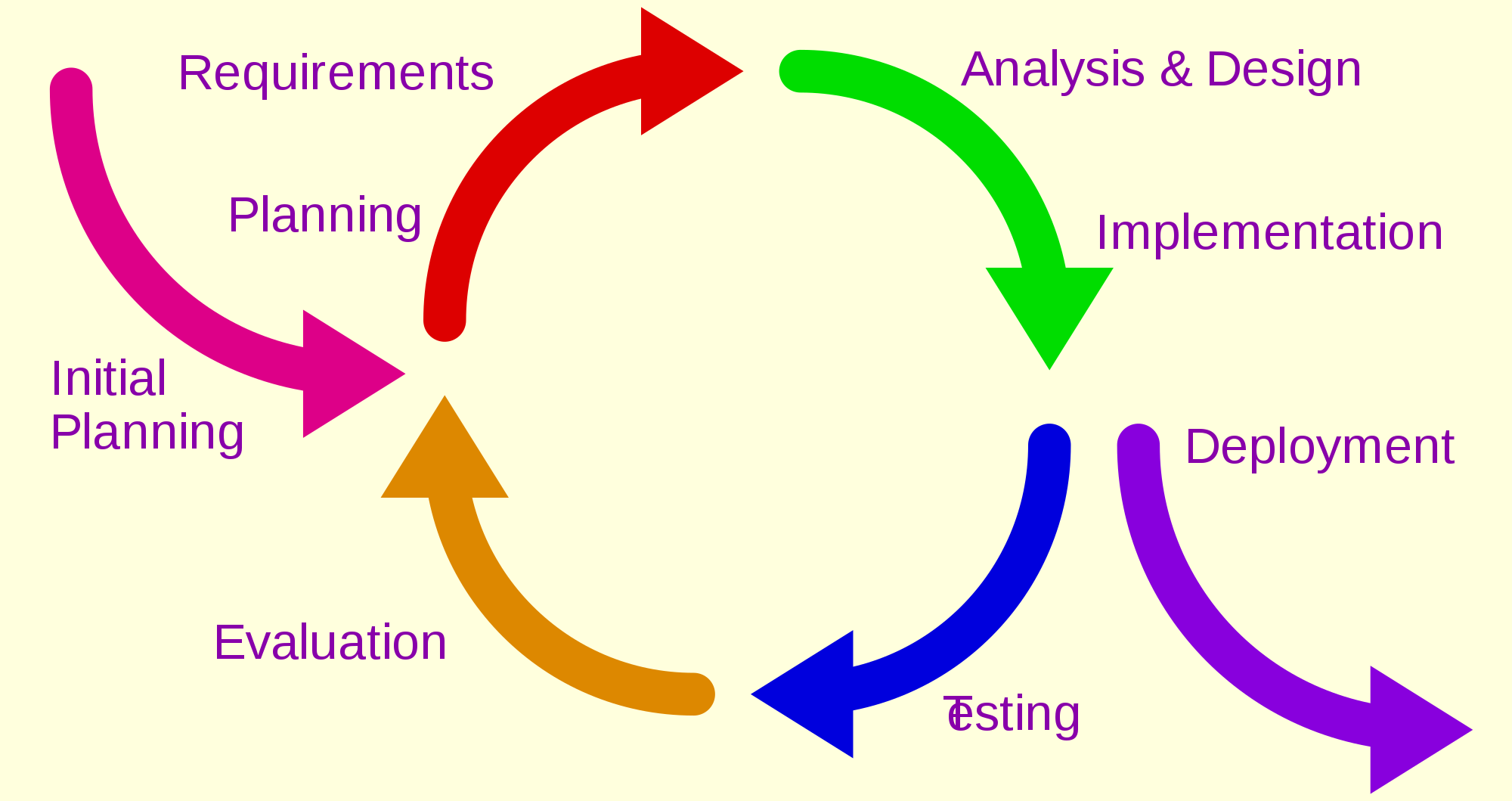

When the kids are explained the challenge, they go in with no egos, no positional titles or perceived genius or specialization. One would think those at the highest levels of organizations or departments would be masters of communication, but it seems titles interfere with their collaboration skills. Therefore, kids focus on the task at hand, paying particular attention to the multiple, expected failure before coming up with a strategy that works. As they fail, they learn quickly and adjust their technique. This type of collaboration is the essence of the iterative process.

|

| The Iterative Process: A process for arriving at a decision or a desired result by repeating rounds of analysis or a cycle of operations. |

With each version, kids get instant feedback about what works and does not work. Children do not base self worth on a single task, and care less about winning than adults do - in fact, we teach children to value winning rather than learning. This should be the fear of the emerging leader - the average adult wastes time thinking about theory, while children are busy learning from application - and learning from application is key to thinking outside of the box .Also, as adults, many of us have lost that understanding of potential failure for simple tasks. The task seems easy; who needs 18 minutes? Therefore, we establish ourselves as smart, listen to everyone else's poor idea and wait until the plebeians listen to us and our great idea; then the infighting begins and by the time an agreed upon technique is found, there's five minutes left.

The example evoked two quotes:

I have not failed. I've just found 10,000 ways that won't work.This is the mindset of a child with critical thinking skills. A team of five and six-year-olds really has nothing to prove alone, if they recognize they are working in a team. The goal is to achieve success together, not for one to shine above the others.

Thomas A. Edison

However, in most workplaces, a parent-child dynamic like this reigns over workers from managers:

Listen, you little wiseacre: I'm smart, you're dumb; I'm big, you're little; I'm right, you're wrong, and there's nothing you can do about it.

From Matilda (1996)

Recalling the discussion on the space shuttle Columbia (blog entry on September 10, 2015), strides to improve values and culture are essential to the success of any program or project implemented by a department or organization, If teams do not feel accepted for their strengths and beliefs, the "ta-da" turns into an "uh-oh," which can be because the weight of the marshmallow topples a structure that went untested, or because an obvious desire flaw called out by engineers was left unfixed and caused seven people to die. Imagine the NASA managers and engineers taking the Marshmallow Challenge and realizing their failure to communicate and respect each others' ideas; perhaps such team building could have save those lives.

Executive Assistants (EAs) perform, coordinate and oversee office administrative duties while providing an extensive level of support to Executive Managers. They help managers make the best use of their time and are relied on heavily to ensure that work is handled efficiently and without the need for constant or direct supervision (Scivicque, 2008). Therefore, EAs allow for managers to stay on task, which is why team with EAs perform better on the Marshmallow Challenge.

As a worker who is not at the top of my institutional ladder or department, it can be difficult to speak up when someone else has more rapport, a higher title, or more education than I do, particularly when it is used to solidify decisions. Power involves the capacity of one party (the "agent") to influence another party (the "target"). An agent may have influence over a single or over multiple target persons. Power comes in many forms, yet fives specific types are prevalent: reward power, coercive power, legitimate power, expert power and referent power (Yukl, 2010). Legitimate, reward and coercive power have one large setback: these positional power structures are easily abused. This abuse involves a manager believing that they are the center of everything, that they know all, and are oblivious to the indirect verbal and nonverbal feedback from employees (Messina, 2008).

Therefore, attitude is the determining factor between success and failure. In much the same way leaders should empower their teams, there is a way to lead from behind and not be intimidated by the formal power of others. EAs usually have this as expert power: they know the inter-workings of the office. Nelson Mandela popularized the concept of leading from behind, a concept most executive and administrative assistants have and departmental leaders are trying to catch up on (Lizza, 2011):

References

Scivicque, Chrissy. (2008). The Effective Executive Assistant A Guide to Creating Long‐Term Career Success. Accessed at https://www.nesacenter.org/uploaded/conferences/SEC/2014/handouts/Rick_Detwiler/20_Detwiler_Resources.pdf

Executive Assistants (EAs) perform, coordinate and oversee office administrative duties while providing an extensive level of support to Executive Managers. They help managers make the best use of their time and are relied on heavily to ensure that work is handled efficiently and without the need for constant or direct supervision (Scivicque, 2008). Therefore, EAs allow for managers to stay on task, which is why team with EAs perform better on the Marshmallow Challenge.

As a worker who is not at the top of my institutional ladder or department, it can be difficult to speak up when someone else has more rapport, a higher title, or more education than I do, particularly when it is used to solidify decisions. Power involves the capacity of one party (the "agent") to influence another party (the "target"). An agent may have influence over a single or over multiple target persons. Power comes in many forms, yet fives specific types are prevalent: reward power, coercive power, legitimate power, expert power and referent power (Yukl, 2010). Legitimate, reward and coercive power have one large setback: these positional power structures are easily abused. This abuse involves a manager believing that they are the center of everything, that they know all, and are oblivious to the indirect verbal and nonverbal feedback from employees (Messina, 2008).

Therefore, attitude is the determining factor between success and failure. In much the same way leaders should empower their teams, there is a way to lead from behind and not be intimidated by the formal power of others. EAs usually have this as expert power: they know the inter-workings of the office. Nelson Mandela popularized the concept of leading from behind, a concept most executive and administrative assistants have and departmental leaders are trying to catch up on (Lizza, 2011):

I always remember the regent’s axiom: a leader, he said, is like a shepherd. He stays behind the flock, letting the most nimble go out ahead, whereupon the others follow, not realizing that all along they are being directed from behind.EAs have special skills of facilitation. They manage the process, they understand the process. And any team who manages and pays close attention to work will significantly improve the team's performance (Wujec, 2010). May we all harness the skills of the EA, while we are still working our way up the ladder, and keep those skills as we gain more power.

References

Scivicque, Chrissy. (2008). The Effective Executive Assistant A Guide to Creating Long‐Term Career Success. Accessed at https://www.nesacenter.org/uploaded/conferences/SEC/2014/handouts/Rick_Detwiler/20_Detwiler_Resources.pdf

Lizza, Ryan. (2011). The New Yorker Online. Accessed at http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/leading-from-behind

Wujec, T. (2010). Build a tower, build a team. Retrieved from

http://www.ted.com/talks/tom_wujec_build_a_tower

Yukl, G. (2010). Leadership in Organizations, 8th edition. Prentice Hall.

http://www.ted.com/talks/tom_wujec_build_a_tower

Yukl, G. (2010). Leadership in Organizations, 8th edition. Prentice Hall.